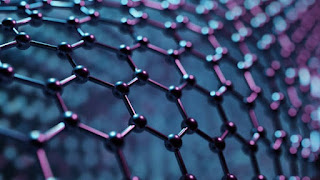

NPL, in collaboration with international partners, has developed an ISO/IEC standard, ISO/TS 21356-1:2021, for measuring the structural properties of graphene, typically sold as powders or in a liquid dispersion.

The ISO/IEC standard allows the supply chain to answer the question ‘what is my material?’ and is based on methods developed with The University of Manchester in the NPL Good Practice Guide 145.

Verified Quality Control Methods

In conjunction with the international ISO/IEC terminology standard led by NPL, ISO/TS 80004-13:2017, it will be possible for commercially available material to be correctly measured and labelled as graphene, few-layer graphene or graphite.

As the UK’s National Metrology Institute, NPL has been developing and standardizing the required metrologically-robust methods for the measurement of graphene and related 2D materials to enable industry to use these materials and realize novel and improved products across many application areas.

The continuation of the NPL-led standardization work within ISO TC229 (nanotechnologies) will allow the chemical properties of graphene related 2D materials to be determined, as well as the structural properties for different forms of graphene material, such as CVD-grown graphene.

This truly international effort to standardize the framework of measurements for graphene is described in more detail in Nature Reviews Physics, including further technical discussion on the new ISO graphene measurement standard.

Dr Andrew J Pollard, science area leader at NPL said, “It is exciting to see this new measurement standard now available for the growing graphene industry worldwide. Based on rigorous metrological research, this standard will allow companies to confidently compare technical datasheets for the first time and is the first step towards verified quality control methods.”

Dr Charles Clifford, senior research scientist at NPL said, “It is fantastic to see this international standard published after several years of development. To reach international consensus especially across the 37 member countries of ISO TC229 (nanotechnologies) is a testament both to the global interest in graphene and the importance of international cooperation.”

James Baker, CEO of Graphene@Manchester said, “Standardization is crucial for the commercialization of graphene in many different applications such as construction, water filtration, energy storage and aerospace. Through this international measurement standard, companies in the UK and beyond will be able to accelerate the uptake of this 21st Century material, now entering many significant markets.”

Source: NPL

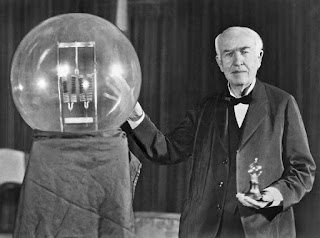

What was the first application of carbon fibers? It's not what you are thinking! 👀

Carbon fibers are older than you imagine! The first carbon fibers date back to 1860! In 1879, a certain guy named Thomas Edison chose carbon fibers to manufacture light bulb filaments. At that time, they were not petroleum-based. Instead, they were produced through the pyrolysis of cotton or bamboo filaments. These filaments were ''baked'' at high temperatures to cause carbonization to take place.

But why were they chosen? The answer is pretty straightforward and has nothing to do with high strength! At the time, Edison noticed that their high heat tolerance made them ideal electrical conductors. However, soon later tungsten took over as the light bulb filament of choice in the early 1900s, and carbon fiber became obsolete for the next 50 years or so.